Introduction

Previous studies reported that an imbalance of the gut microbiota with a relative increase in Firmicutes versus Bacteroidetes is associated with the pathogenesis of obesity [1]. A Firmicutes predominance can lead to increased production of metabolites from nondigestible polysaccharides, predisposing the host to enhanced energy extraction and augmenting weight gain [2]. This shift has also been associated with increased production of shortchain fatty acids (SCFA) and inflammation, both of which can contribute to the development of obesity and related metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. The role of SCFA in the onset of gut dysbiosis is described below.

Role of metabolites associated with gut dysbiosis

A growing body of evidence supports the concept that a disruption of the gut microbiota early in life can increase the likelihood of chronic diseases, including obesity. The first bacteria to colonize the intestinal tract at birth are obligate anoxic bacteria such as Bifidobacterium spp. and Bacteroides spp. Newborns born via cesarean section (CS) are initially exposed to bacteria in the external environment and skin microorganisms (e.g., Staphylococcus spp. and Corynebacterium spp.), whereas newborns born vaginally are exposed to the mother’s vaginal/fecal microflora. Therefore, newborns born vaginally have more diverse and numerous microorganisms, including Bifidobacterium spp., than newborns born by CS [3]. There is a strong association between CS and an increased body mass index (BMI) of the offspring and overweight and obesity in adulthood [4].

Cho et al. [5] reported that administering low doses of antibiotics to young mice increased adiposity and the levels of hormones involved in energy metabolism. Neonatal antibiotic exposure may be associated with these complications. Furthermore, dysbiosis is associated with microbial genes associated with SCFA production and increased colonic SCFA levels. The prominent SCFAs include acetate, propionate, and butyrate. Butyrate serves as an energy substrate for colonocytes, propionate contributes to hepatic gluconeogenesis, and acetate is utilized by the peripheral tissues [6]. SCFAs have also been shown to regulate appetite and satiety hormones, which can affect food intake and energy balance. However, the exact mechanisms by which SCFA contribute to obesity are not fully understood, and further research is required to elucidate their roles in this complex disease.

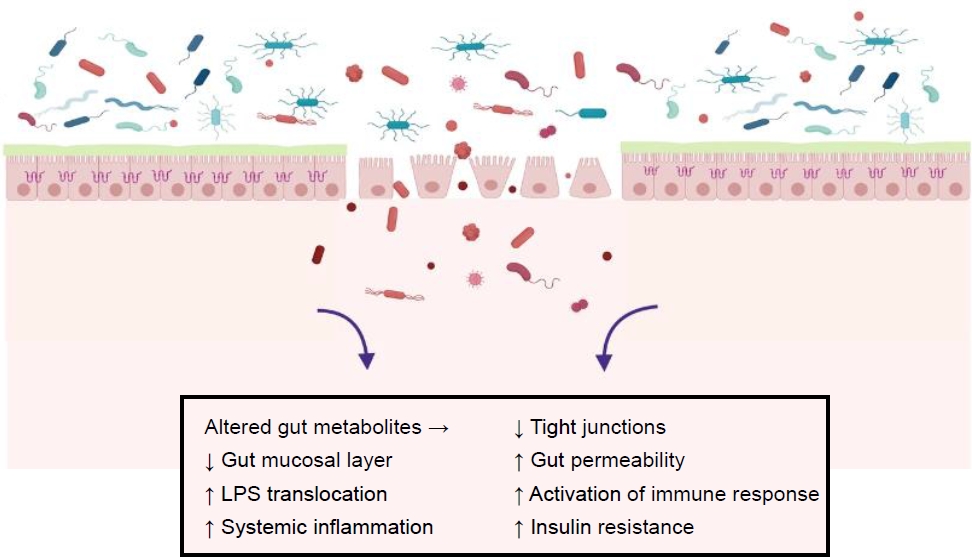

An altered gut microbiota can modulate gut permeability, resulting in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) translocation, which can initiate low-grade inflammation in the host [7]. LPS is a component of the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria, mainly including the phylum Proteobacteria and the genera Bacteroides and Prevotella. LPS plays an important role in the inflammatory process by activating the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4, which is expressed by macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells. Altered TLR-4 signaling leads to the activation of further downstream pathways, including nuclear factor-κB and proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α propagating the cascade of further inflammation and promoting insulin resistance. A dietary highfat intake is reportedly associated with increased plasma LPS [8]. Fig. 1 summarizes the prominent pathogenic factors related to the development of obesity and obesity-related disorders.

Impact of interventions on the gut microbiota

Pre- and probiotics also increase the microbial diversity within the gut, improve insulin sensitivity, and reduce LPS activation. Few pediatric studies have assessed the effects of probiotics on obesity and anthropometric indices. A 1-month intervention with synbiotics significantly decreased the weight and BMI of obese children and adolescents [9]. An 8-week intervention with Lactobacillus rhamnosus in obese children with the liver disease showed that L. rhamnosus GG altered the bacterial composition without any remarkable effect on the BMI z score or visceral fat. However, a 12-week intervention with Lactobacillus salivarius (Ls-33) had no significant influence on BMI z score, waist circumference, or body fat in adolescents [10]. The differences between studies could be due to variations in probiotic strains, supplement compositions, and doses, subjects’ characteristics, geographical variables, and interventional duration. In a recent meta-analysis evaluating 25 studies, 11 noted that prebiotics improved systemic inflammation in obesity. Although fecal microbiota transfer has shown promise in animal studies involving metabolic conditions, more clinical trials are required to determine its efficacy.

Future directions

The exact mechanisms of obesity are conflicting and have varied among different study models. The associations reported in human studies have not demonstrated causation. Future research on utilizing other omics technologies (metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) will aid the further characterization and exploration of the metabolic activity of the microbiota.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation