Article Contents

| Clin Exp Pediatr > Volume 66(11); 2023 |

|

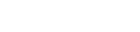

Abstract

Background

Purpose

Methods

Results

Footnotes

Funding

This work was financially supported by The Health System Research Institute, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, Thai Clinical Trial Registry: TCTR20191009001.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: P.Sarisuta, IC; Data curation: P.Sritipsukho; Formal analysis: TH; Funding acquisition: P.Sritipsukho; Methodology: P.Sarisuta; Project administration: P.Sritipsukho; Visualization: P.Sarisuta, TH; Writing – original draft: P.Sarisuta; Writing – review & editing: P.Sarisuta, IC

Acknowledgments

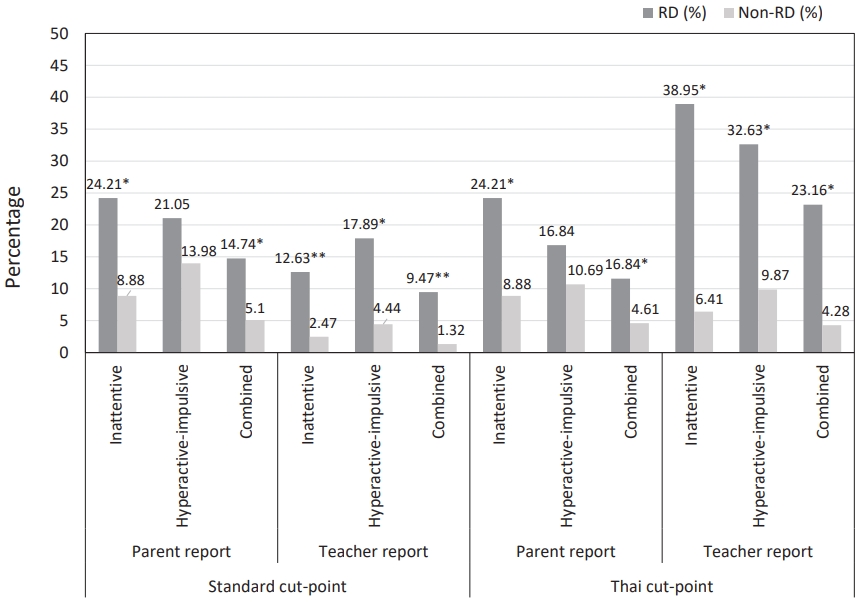

Fig. 1.

Table 1.

| Variable | Reading disorder (n=95) | Nonreading disorder (n=608) | Total | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | <0.001† | |||

| Female | 26 (27.4) | 327 (53.8) | 353 (50.2) | |

| Male | 69 (72.6) | 281 (46.2) | 350 (49.8) | |

| Age (yr) | 6.52±0.76 | 6.57±0.53 | 6.56±0.57 | 0.523† |

| Maternal education | 0.044† | |||

| High school or lower | 68 (77.3) | 387 (66.5) | 455 (67.9) | |

| Vocational college or higher | 20 (22.7) | 195 (33.5) | 215 (32.1) | |

| Paternal education | 0.058† | |||

| High school or lower | 65 (78.3) | 385 (68.0) | 450 (69.3) | |

| Vocational college or higher | 18 (21.7) | 181 (32.0) | 199 (30.7) | |

| Average family income per month (USD) | 0.030† | |||

| <285 | 30 (33.7) | 115 (19.8) | 145 (21.6) | |

| 285–855 | 43 (48.3) | 299 (51.5) | 342 (51.0) | |

| 855–1,425 | 10 (11.2) | 110 (18.9) | 120 (17.9) | |

| 1,425–2,850 | 4 (4.5) | 45 (7.8) | 49 (7.3) | |

| >2,850 | 2 (2.3) | 12 (2.1) | 14 (2.1) | |

| Kindergarten school | 0.135‡ | |||

| Attend | 88 (97.8) | 580 (99.5) | 668 (99.3) | |

| Not attend | 2 (2.2) | 3 (0.5) | 5 (0.7) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Delayed speech history | <0.001‡ | |||

| Yes | 13 (15.8) | 21 (3.8) | 34 (5.4) | |

| No | 69 (84.2) | 533 (96.2) | 602 (94.6) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2.2) | 8 | 10 | |

| Family history of reading or writing difficulty | 0.001† | |||

| Yes | 21 (22.1) | 62 (10.2) | 83 (11.8) | |

| No | 74 (77.9) | 546 (89.8) | 620 (88.2) | |

| Unknown | 8 | 21 | 29 | |

| Parents’ perception of their child’s reading ability | <0.001† | |||

| Inferior | 37 (55.2) | 46 (8.9) | 83 (14.3) | |

| Normal | 29 (43.3) | 433 (84.1) | 462 (79.4) | |

| Superior | 1 (1.5) | 36 (7.0) | 37 (6.3) | |

| Unknown | 24 | 73 | 97 | |

| School affiliation | 0.001† | |||

| Office of Basic Education | 34 (35.8) | 124 (20.4) | 158 (22.5) | |

| Local Administration Organization | 34 (35.8) | 219 (36.0) | 253 (36.0) | |

| Private schools | 27 (28.4) | 265 (43.6) | 292 (41.5) |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

USD, United States dollar.

Students at risk of reading disorders were defined as those whose sum score of the word reading or the 3-passage reading test was ≤10th percentile of the sampled population.

Some students' parents did not intend to provide information about their education, incomes, attending kindergarten school, etc., so, these categories are absent in the questionnaires.

Boldface indicates a statistically significant difference with P<0.05.

Table 2.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

The data were analyzed using an independent t test.

SNAP-IV, Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham IV Rating Scale; ADHD, attentiondeficit/hyperactive-impulsive disorder.

Students at risk of reading disorders were defined as those whose sum score of the word reading or the 3-passage reading test was ≤10th percentile of the sampled population.

Boldface indicates a statistically significant difference with P<0.05.

Table 3.

With reference to nonreading disorder group.

Adjusted for confounders including sex, maternal education, average monthly family income, delayed speech history, family history of reading or writing difficulty, parents’ perception of child’s reading ability, and school affiliations.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactive-impulsive disorder; SNAP-IV, Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham IV Rating Scale; CI, confidence interval.

The standard cutoff criteria of the teacher version for children with ADHD were predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentations, and oppositional defiant disorder were 23, 16, and 11, respectively, while those of the parent version were 16, 13, and 15, respectively.

Boldface indicates a statistically significant difference with P<0.05.

Table 4.

With reference to the nonreading disorder group.

Adjusted for confounders including sex, maternal education, average monthly family income, delayed speech history, family history of reading or writing disorder, parents’ perception of child’s reading ability, and school affiliations.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity-impulsivity disorder; SNAP-IV, Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham IV Rating Scale; CI, confidence interval.

The Thai cutoff criteria of the teacher version for children with ADHD were predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentations, and oppositional defiant disorder were 18, 11, and 8, respectively, while those of the parent version were 16, 14, and 12, respectively.

Boldface indicates a statistically significant difference with P<0.05.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation