Article Contents

| Clin Exp Pediatr > Volume 69(1); 2026 |

|

Abstract

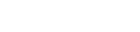

The ingestion of foreign bodies and caustic substances represents a significant clinical concern in pediatric populations, particularly among children aged 1–5 years. These events can result in a wide spectrum of complications ranging from acute, life-threatening emergencies to delayed sequelae with long-term morbidities. The severity and clinical course are influenced by multiple factors, including ingested material’s nature, size, shape, and chemical composition, as well as its anatomical location, particularly when esophageal impaction occurs. High-risk foreign bodies— such as button batteries, high-powered magnets, sharp objects, superabsorbent polymers, and items containing toxic substances—pose an elevated risk of rapid tissue injury or perforation. Similarly, the ingestion of caustic agents, whether acidic or alkaline, carries the potential for extensive mucosal damage, with the degree of injury dictated by the pH, volume ingested, and inherent toxicity. Clinical management requires a highly individualized, case-by-case approach guided by the clinical presentation, imaging findings, and endoscopic evaluation findings. Endoscopy plays a pivotal role in the diagnostic assessment of mucosal injury and is a therapeutic modality for foreign body retrieval. Timely endoscopic interventions are strongly associated with improved outcomes and reduced complication rates. A high index of clinical suspicion remains critical to ensuring early diagnosis, prompt intervention, and the prevention of both acute and long-term complications, including strictures, perforations, and impaired quality of life. Comprehensive, multidisciplinary management is essential for optimizing patient outcomes in these potentially complex clinical scenarios.

Graphical abstract

The majority of cases of foreign body ingestions in children occur between the ages of 6 months and 3 years [1-3]. In most cases, the ingestion is reported by the child's caregivers or other family members as witnesses or suspects of the event. Its clinical management focuses on confirming and treating cases at risk of complications, depending on the foreign body's type and location. The ingestion of caustic substances is a frequent concern in emergency departments, occurs most often in children aged 1–3 years and can cause serious acute and long-term complications, such as the development of esophageal strictures [4,5].

More than 100,000 cases of foreign body ingestion are reported annually in the United States (US) and of them, >75% occur during childhood [1,6,7]. Most foreign body ingestions occur between the ages of 6 months and 3 years [1-3]. Multiple body ingestions and repeated episodes are uncommon and mainly observed in children with neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorders [8,9]. Although the mortality rate from foreign body ingestion is extremely low, deaths have been reported [2,10]. Common foreign bodies swallowed by children include coins, button batteries, toys, toy parts, magnets, safety pins, screws, jewelry, bones, and food [2,7,11].

The consumption of flat batteries (Fig. 1B) has recently increased because of their widespread use in household appliances and other devices. Serious complications (esophageal burns, perforation, and/or fistula development) and/or death occur in 3% of battery ingestion cases [2,3,13]. Although disc-shaped batteries have been used for almost 30 years, their initial clinical experience with ingestion quite benign. Data collected and published by the National Capital Poison Centre in 1992 on >2,300 patients showed that over a 7-year period no deaths occurred and only 0.1% of affected individuals developed a serious complication consisting of 2 esophageal strictures [14]. However, over the next 20 years, clinical experience has changed dramatically with a new follow-up study from the same center. In this study of >8,600 cases, major complications occurred in 73 patients (0.8%), versus death in 13 patients (0.15%) [15]. The cause of this dramatic increase in morbidity and mortality appears to be linked to 2 specific changes in the market during this period: increased battery diameter and the change to lithium cells which cause an increased likelihood of esophageal impaction and increased pressure respectively. Lithium batteries >20 mm are responsible for 94% of battery ingestion-related deaths. The tissue damage is caused by the generation of hydroxide radicals; therefore, caustic mucosal damage is induced by from a high pH rather than electrothermal injury. Changes including, an increase in pH from 7 to 13 at the negative pole in 30 minutes and mucosal necrosis in 15 minutes [16] were observed in animal experiments.

These findings are compatible with reports of esophageal strictures at 2 hours after ingestion and highlighting the importance of immediate endoscopic interventions in these children.

Sharp objects (Fig. 1C) constitute 10%–15% of the foreign bodies swallowed by children [7]. The most common sharp objects are safety pins, needles, paper clips, pins, and fish bones. Sharp objects carry a high risk of perforation of approximately ~15%–35% [1,17]. If such objects lodged within the hypopharynx, they can cause a retropharyngeal abscess [18]. Toothpicks and bones also frequently cause perforations [7,19].

Impacted food (Fig. 1D) is the most common foreign body in the esophagus of adults but not in children. Children with bolus impaction usually have underlying esophageal pathologies such as: eosinophilic esophagitis, esophagitis caused by reflux, strictures, achalasia, diaphragm or ring, or esophageal motility disorders [7,20,21]. Therefore, biopsy is recommended, during endoscopy for bolus removal, biopsies in these also recommended [7].

In recent years, use of magnets has increased in toys consisting of small hundreds of balls, cylinders or cubes, “stress relievers” and household utensils, resulting in serious consequences from swallowing them [22,23]. These magnets are high-powered, are made of neodymium and exert 5 times the pulling force of traditional magnets. This risk arises because the as the mucous membrane can become trapped between the magnets or between the magnet and another metal body, causing perforation and fistula.

Objects/toys comprising of many parts require special attention because they may include radio-opaque or nonradioactive parts or even batteries with known risks, such as the fidget spinner toy [24].

Long objects such as toothbrushes, batteries, and spoons are more commonly swallowed by older children, adolescents, and adults. The risk of serious complications depends on the object's length or other characteristics as well as the child's age [25].

Objects with a high lead content (e.g., lead weights used in fishing, curtain weights, toys, medals) can cause acute lead poisoning, or even death [26].

Children are often asymptomatic after foreign body ingestion, in which case the investigations are performed because of a positive or suspected history. In a study of 325 pediatric patients, only 50% with a foreign body in the esophagus reported symptoms, such as retrosternal pain, dysphagia, and cyanosis at the time of swallowing, in many of these children, these symptoms were transient [18]. When symptoms are present, the clinical presentation varies according to foreign body and location.

When a foreign body is present in the esophagus, a child may experience food intake refusal, dysphagia, drooling, chest pain, restlessness or respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, hoarseness and fever. Sharp foreign bodies, may cause symptoms such as subcutaneous emphysema or even pneumomediastinum due to esophageal perforation [2,12]. In cases in which the foreign body has been lodged within the esophagus for an extended long time, weight loss, recurrent aspiration pneumonia, or tracheoesophageal fistula development may occur. Aortic erosion and life-threatening bleeding after the ingestion of foreign bodies have also been described [20].

Patients with a foreign body in the stomach are usually asymptomatic, unless that foreign body is large and capable of causing an obstruction, which would result in vomiting or even a refusal to eat [27]. Patients with a gastric outlet obstruction may present with emesis containing undigested gastric contents as well as, non-bilious, gastric distension. Depending on the type of foreign body (e.g., sharps, batteries, magnets), its removal is considered advisable even in asymptomatic patients to avoid further complications.

Foreign bodies that pass through the pylorus and progress into the intestine usually do not cause symptoms and are expelled during defecation. In some cases, they can become trapped in the lower digestive tract, causeinge delayed complications. Cases of coin entrapment in the cecum with symptoms compatible with appendicitis, pyogenic liver abscess after the displacement of a sharp object from the digestive tract, chronic appendicitis after the insertion of a long object, and ileal perforation after swallowing a stone have been described.

A detailed history and meticulous physical examination are crucial in the case of a suspected foreign body and ensure an appropriate investigation. Increased clinical suspicion is also very important when the corresponding symptomatology is present, even with a negative history in patients within high-risk age groups (children up to 3–5 years of age), for whom foreign body ingestion should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Conventional anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the neck, chest, and abdomen can be used to establish at diagnosis and provide information regarding foreign body type and location [2,15]. A metal detector can reveal materials that are metals but not radiopaque, for example. aluminum; however, it has limited diagnostic value as it does not detect all metallic bodies [28] and cannot specify its type (e.g., battery versus/coin, or exact location.

When the presence of a foreign body is revealed on radiography, the following should be evaluated. First, the location of the foreign body should be determined to inform its appropriate management. Foreign bodies located within the esophagus should be differentiated according to tracheal or esophageal placement. Flat foreign bodies located in the trachea tend to assume a sagittal position and are best observed on lateral radiographs, whereas those located in the esophagus are usually oriented coronally and appear circular on anteroposterior radiographs [29].

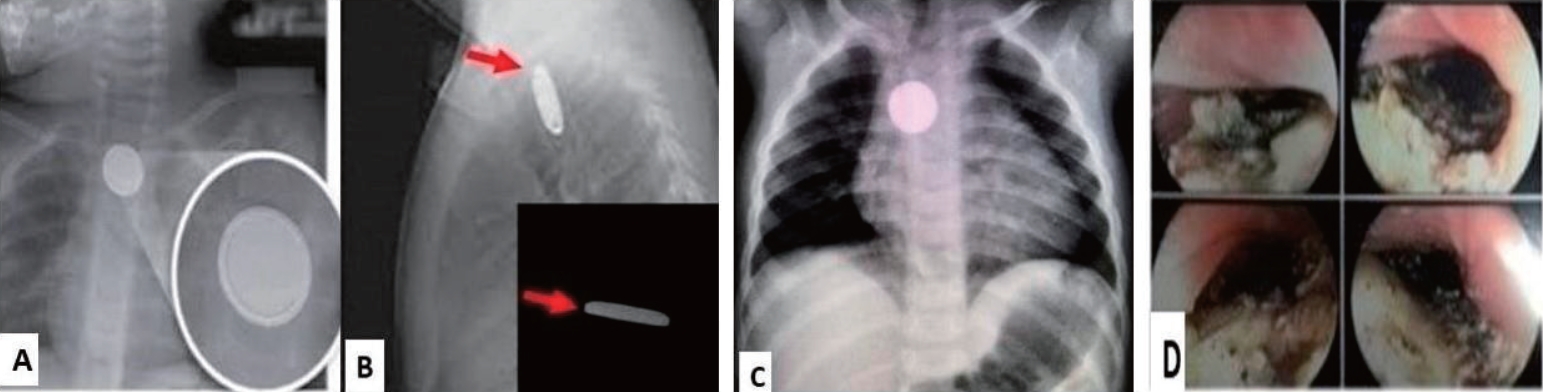

Equally important is the distinction between circular foreign bodies in the esophagus, as batteries require immediate removal, whereas coins may not. For batteries, the double-halo or step-off sign Fig. 3 is characteristic. If simple radiographs cannot identify the foreign body, further investigation using computed tomography (CT) or noncontrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be required especially if the patient is symptomatic or the foreign body has some dangerous characangiograteristics such as being sharp, long >5 cm. or large, (diameter >2 cm). If the patient is asymptomatic, the environment is reliable and safe for the ingested foreign body, and the object has benign characteristics, further imaging may not be necessary. The use of ultrasound to highlight a foreign body in the esophagus or stomach requires appropriate special operator experience [30]. Upper gastrointestinal transit with water-soluble contrast has been used to highlight mainly nonradioactive foreign bodies, whereas barium transit should be avoided since it may complicate localization of the foreign body during any upcoming gastroscopy.

Patient management in such cases varies depending on the patient’s clinical picture, age, as well as the, foreign body's location, properties, size, length, sharpness. Foreign body type dictates the specific instructions for the timing of its removal.

A small percentage of swallowed coins are found in the esophagus, whereas approximately two-thirds of them are found in the stomach during initial radiography. If in the esophagus, they should be removed immediately if the patient is symptomatic or within 24 h if the patient is asymptomatic. Typically, in 20%– 30% of cases, the coin advances into the stomach during follow-up; this, this occurs more often in older children and when initially located in the lower third of the esophagus [31].

When coins are found in the stomach, treatment can be conservative because they have smooth borders, are not made of toxic metals, and in the majority of cases, they are expelled naturally without complications within 1–2 weeks. If the coin remains in the stomach for >4 weeks, its surgical removal is recommended [1,7,15]. If the patient presents with symptoms, such as vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain, the coin's condition and location are reassessed and endoscopic removal is performed.

A battery in the esophagus is a medical emergency that should be treated immediately. Esophageal necrosis can be caused by battery liquefaction through an electrical current, resulting in ulceration within a few hours and perforation of the esophagus up to 8 h after ingestion [24]. Therefore, if a battery is lodged in the esophagus, immediate removal within 2 hours is recommended. If immediate access to an endoscopic room is lacking, it is recommended that children >1 year of age, who are not allergic, be administered a single dose (of 5–10 mL) of honey by the parents as soon as possible after the battery is swallowed (especially if the child is being transported from the countryside), followed by a single dose of sucralfate 500 mg once the hospital is reached. Animal studies have shown that honey has a protective effect against the appearance of burn damage [32]. Patients with a battery embedded in the esophagus requires hospitalization, immediate endoscopic removal, and special imaging when deemed necessary to detect possible complications, such as esophageal perforation, tracheoesophageal fistula, and aortic erosion [15]. In cases of severe esophageal burns, must be re-evaluated for esophageal strictures. The usual practice is to perform a barium swallow at 4–6 weeks after battery ingestion.

According to recent ESPGHAN guideline the protocol for treating battery ingestion in children [33] when the battery is postesophageal, the distinction is made according to the time that has passed since the battery was swallowed. If it is <12 hours have passed and the child is symptomatic or swallowed a magnet, immediate endoscopy within 2 hours is recommended. If the battery passed through the stomach, then a pediatric surgery consult is recommended. If the child is asymptomatic, then radiograph should be repeated at in 7–14 (earlier if symptoms occur). Management is individualized for each case and center. If >12 hours have passed since the episode, endoscopy is recommended to remove the battery and to assess possible damage to the esophageal mucosa. If transmural esophageal damage is suspected, CT angiography is recommended to exclude the possibility of vascular damage.

If a battery is detected in the stomach, it is removed. If it has progressed to the intestine and the child is symptomatic then, pediatric surgical treatment is recommended; however, if the child is asymptomatic, continued radiographic monitoring for 7–14 days is recommended.

Food impaction in the esophagus (Fig. 1D) is rare in children and usually conceals esophageal pathologies. Food removal is performed immediately when children cannot manage their secretions; if the patient feels comfortable and manages their secretions removal can be extended to <24 hours [7], and treatment is individualized depending on food type and impaction location [21]. However, the use of proteolytic enzymes, such as, papain or glucagon, is not recommended for the management of food impaction in children.

Magnet swallowing (Fig. 2) is a serious and sometimes life-threatening problem requiring that requires special management. Swallowing one or more high-powered magnets, especially if swallowed at different times, can trap the mucosa, through an attractive force between them, resulting in pressure, necrosis, perforation, inflammation, obstruction and further complications such as bowel resection. Magnet ingestion requires immediate evaluation using, cervical, thoracic, abdominal, and lateral radiographs. Mucosal entrapment cannot always be assessed using radiography; however, the consistent presence of slightly separated magnets is indicative of this issue. Even when a single high-power magnet is swallowed, there is a risk of mucosal entrapment may occur due to internal or external contact with another metal object on the individual's clothing, jewelry, or belts. Repeated radiographs are then used to determine whether are multiple magnets which may mistakenly suggest that they are one (fused together). Thus, immediate removal from the esophagus, stomach, or proximal duodenum is recommended if multiple magnets or other metallic objects have been swallowed. I case the magnets have advanced into the intestine, asymptomatic patients should undergo close clinical monitoring and radiographs every 4–6 hours. Alternatively, an attempt should be made to remove them using enteroscopy or colonoscopy if feasible. If patients are symptomatic, immediate surgical resection is recommended.

The removal of long and blunt objects, such as toothbrushes, batteries, and spoons, should be individualized depending on their length and width as well as child's age. Objects >6 cm usually cannot pass through the stomach [13], and their removal is recommended. However, close monitoring and surgical treatment are required if these objects enter the intestine. In children aged <5 years, removal from the stomach is recommended if the objects are >2.5 cm long.

Superabsorbent objects (Fig. 1F) have the ability to increase their volume by 30–60 times upon contact with liquids. These objects are not radiopaque and radiographs do not help locate them in the digestive tract. The administration of a water-soluble contrast agent may highlight their location and size. Their immediate removal is recommended due to the increased risk of obstruction, if endoscopic removal is not possible or the patient's symptoms warrant surgical treatment.

Acute lead poisoning can occur in children who swallowed lead-containing objects. Elevated levels of lead were found even 90 minutes after ingestion as the acidic environment of the stomach favors the dissolution of the metal. Thus, the immediate removal of these objects from the esophagus or stomach is recommended.

The indications for immediate removal of the foreign bodies are shown in Table 1

Different methods can be used to remove foreign bodies depending on object size and location; However, in some cases, they are expelled naturally. A rigid endoscope is typically used for foreign bodies located proximal to the upper esophageal sphincter. Magill forceps can also be used to retrieve foreign bodies located in the oropharynx and proximal to the upper esophageal sphincter that are visible during the intubation phase.

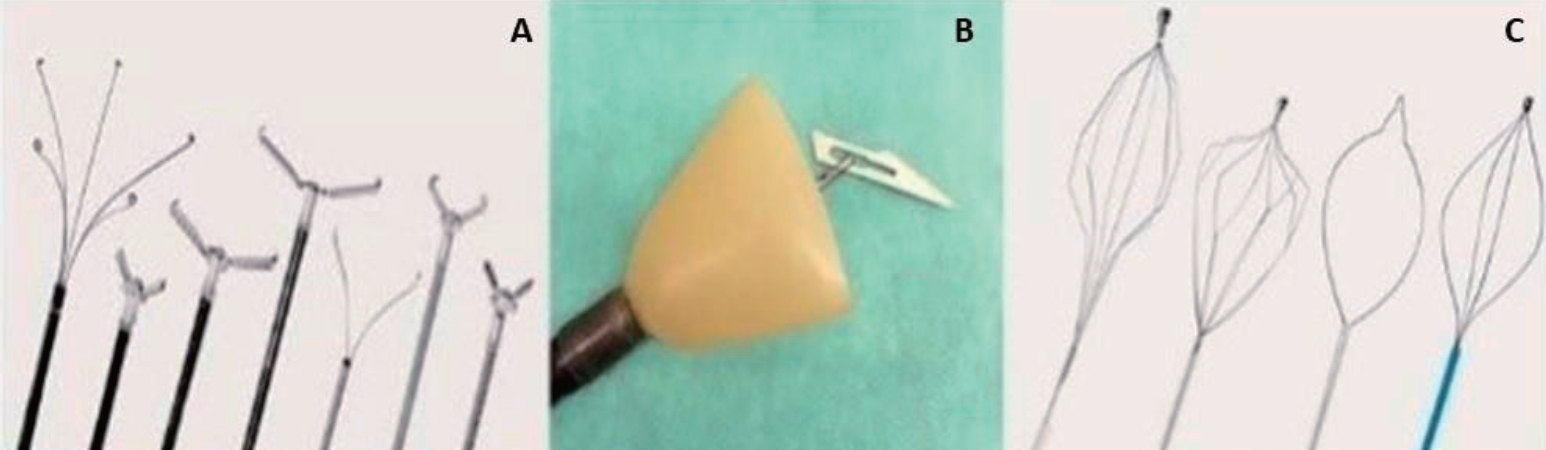

Flexible endoscopes preferred in most cases because they can be used to diagnose complications. Depending on the object's type and location, special grasping forceps, loops, and foreign body grasping nets [1,2,8] can also be used (Fig. 4). Older techniques using Foley catheter and forceps through a nasogastric catheter under radiological guidance have been abandoned. In rare cases, surgical intervention may be required to remove foreign bodies (such as magnets) and treat complications.

Foreign body ingestion by children can be a life-threatening situation thus treatment should be individualized depending on the object's location, type and size to prevent complications.

A detailed algorithm for the management of foreign body ingestion in children is presented in Table 2

The accidental ingestion of caustic substances continues to be a problem that requiring immediate treatment and intervention.

Data from the US indicate 2.1 million cases, half of which were in children aged <5 years [34]. The most common substances ingested by children include household items, cosmetics and personal care products. The ingestion of caustic substances is most common in children aged 1–3 years, with 50%–62% of cases occurring in boys [5]. In children, it usually occurs accidentally; while in adults and adolescents it may occur as a suicide attempt.

A substance is classified as caustic when it is capable of causing burns or mucosal erosion owing to its strong acidic or basic properties. Commonly ingested caustic substances include household cleaning products such as bleach, oven cleaners, and drain and toilet cleaners which contain sodium and potassium hydroxide [4]. Other common cleaning products such as laundry and dishwasher detergents, contain sodium phosphate, sodium carbonate, and ammonia [35]. Caustic substances are also components of cosmetic products such as hair care products, and swimming pool products. Alkaline substances are ingested more commonly than acids.

Alkaline and acidic, substances which are caustic, can cause similar mucosal damage similar to that, caused, however, by different mechanisms.

Alkaline substances tend to cause mucosal damage a pH >11.5–12.5 by creating necrosis through liquefaction. This type of necrosis leads to rapid mucosal degradation, allowing deeper penetration and even perforation. Penetration of the esophageal mucosa by an alkaline substance depends on its concentration and contact duration [36].

Corrosive (acidic) substances tend to damage the esophageal mucosa at a pH <2, thereby causing necrosis through thrombosis. Compared to alkaline substances, acidic substances are less likely to cause perforation because clots forming on the mucosal surface prevent further mucosal erosion. However, 6%–20% of acid ingestions cause esophageal burns [4,5,36].

In the first week post ingestion, in addition to the initial damage, delayed damage to the esophagus (either from alkalis or acids) can occur owing to further inflammation and vascular thrombosis. In the next phase, after 10 days, granulation tissue is formed and the esophageal wall thins. During this period, the esophagus is vulnerable to perforation. Esophageal burns are the most serious injuries as they are accompanied by chronic complications and present in 18%–46% of cases of the ingestion of caustic substances among children [37]. After 3 weeks, fibrous tissue formation begins and stenosis may develop in the esophagus, while perforation is less likely. No clear picture of the incidence and severity of gastric damage in such cases is available; however, in a study of 156 children with caustic substance ingestion, 11% suffered esophageal and gastric damage whereas 9% had gastric damage only [38]. In 80% of patients with alkaline ingestion, gastric injury was observed when a large volume (of 200–300 mL) was ingested. Large volume ingestion has been associated with gastric perforation, while bleeding and death from bronchial vein corrosion have been reported [39]. Gastric damage appears to be more severe with the ingestion of acids such as sulfuric acid, which can cause severe propyloride burns and lead to pyloric obstruction [39]. In a review of 98 patients who ingested acid, 8.2% developed gastric obstruction by 27 days, post ingestion and required a gastrojejunal catheter [40].

Postingestion symptoms vary depending on the degree of damage to the digestive tract. The most common symptoms may last for several weeks and include dysphagia, esophageal motility disorders, and prolonged emptying time. Other symptoms include drooling, retrosternal or abdominal pain, or hematemesis.

It is important to clarify the timing of the ingestion of caustic substance, as well as its exact chemical composition, pH, and possible volume ingested. Physical examination should include assessment of the central nervous system, vital signs, pupillary reflexes, and level of consciousness. The symptoms of salivation and refusal to eat suggest an esophageal injury. Lesions to the lips or mouth and pharynx have low predictive value for the presence or absence of esophageal injury. Other parameters requiring consideration include the possible toxic effects of these substances, possibility of intentional ingestion-suicide attempts, and simultaneous intake of multiple substances.

Includes chest and abdominal radiographs are used to assess respiratory function, complications such as gastric or esophageal perforation, and the presence of pneumomediastinum or subcutaneous emphysema. The administration of contrast agents is not recommended; however, if perforation and or emphysema occurs possible erosion of vascular branches are suspected, CT or MRI should be performed.

Patient stabilization and close monitoring are initially recommended, with an emphasis on avoiding vomiting and possible aspiration.

The provocation of vomiting, or administration of milk, water or other neutralizing agents, such as, activated charcoal is not recommended. Patients without signs or symptoms should be monitored for food avoidance and fluid intake [5]. The monitoring period is very important for the further management of the patients. An endoscopic examination is recommended for all symptomatic patients, whereas asymptomatic patients should also be evaluated and endoscopically examined depending on caustic substance type. Depending on lesion and burn extent and severity feeding can be interrupted, and broad-spectrum antibiotics, and drugs that suppress HCl acid production proton pump inhibitors can be administered. The placement of a nasogastric/jejunal catheter under endoscopic guidance may be a feeding option. The use of corticosteroids remains controversial; however, in patients with severe esophageal burns classified as grade ≥2B according to the endoscopic esophageal burn assessment scale [41], their administration may be considered. The ESPGHAN guidelines recommend a short course of high-dose corticosteroids—typically for 3 days—in patients with deep circumferential injuries to potentially reduce the risk of stricture formation [42].

The role of sucralfate in preventing caustic agent-induced strictures is controversial, and limited studies have been conducted to date. A recent study showed that sucralfate significantly reduced the incidence of esophageal stricture following the ingestion of caustic agents in children versus control treatment. High doses of sucralfate therapy for grade IIB esophageal injury, can improve prognosis and reduces the risk of stricture formation [43].

In the next phase, after the injury, an upper gastrointestinal series are recommended to identify strictures and appropriate treatment dilations.

The ingestion of caustic substances in children may be accompanied by immediate or long-term complications. Immediate complications are related to the type of substance type, the damage degree and substance location (esophagus or stomach) and potentially life-threatening. Late complications include the occurrence of esophageal strictures, development of esophageal carcinoma in 2% of patients with very severe lesions, and pyloric stenosis.

In conclusion, esophageal burns are the most serious injuries following the ingestion of caustic substances. The most common causes are alkaline and acidic cleaning substances. After the initial necrosis, further mucosal degradation is observed during the first week post ingestion. Additionally, the ingestion of foreign bodies poses several risks depending on object type, shape and size of. Batteries, magnets, sharp objects, and lead-containing objects containing are considered more dangerous; however, even the most “innocent” ones can cause serious complications depending on their location.

Recent management strategies emphasize urgent endoscopic removal of high-risk foreign bodies such as esophageal button batteries and multiple high-power magnets; early endoscopy for symptomatic caustic ingestions; the avoidance of procedures during the high-risk tissue fragility window and the use of standardized clinical pathways to guide risk stratification, imaging, and timely intervention. The pediatrician’s role is very important in educating parents about implementing, strategies to prevent their children from, having easy access to caustic substances and dangerous foreign bodies.

Footnotes

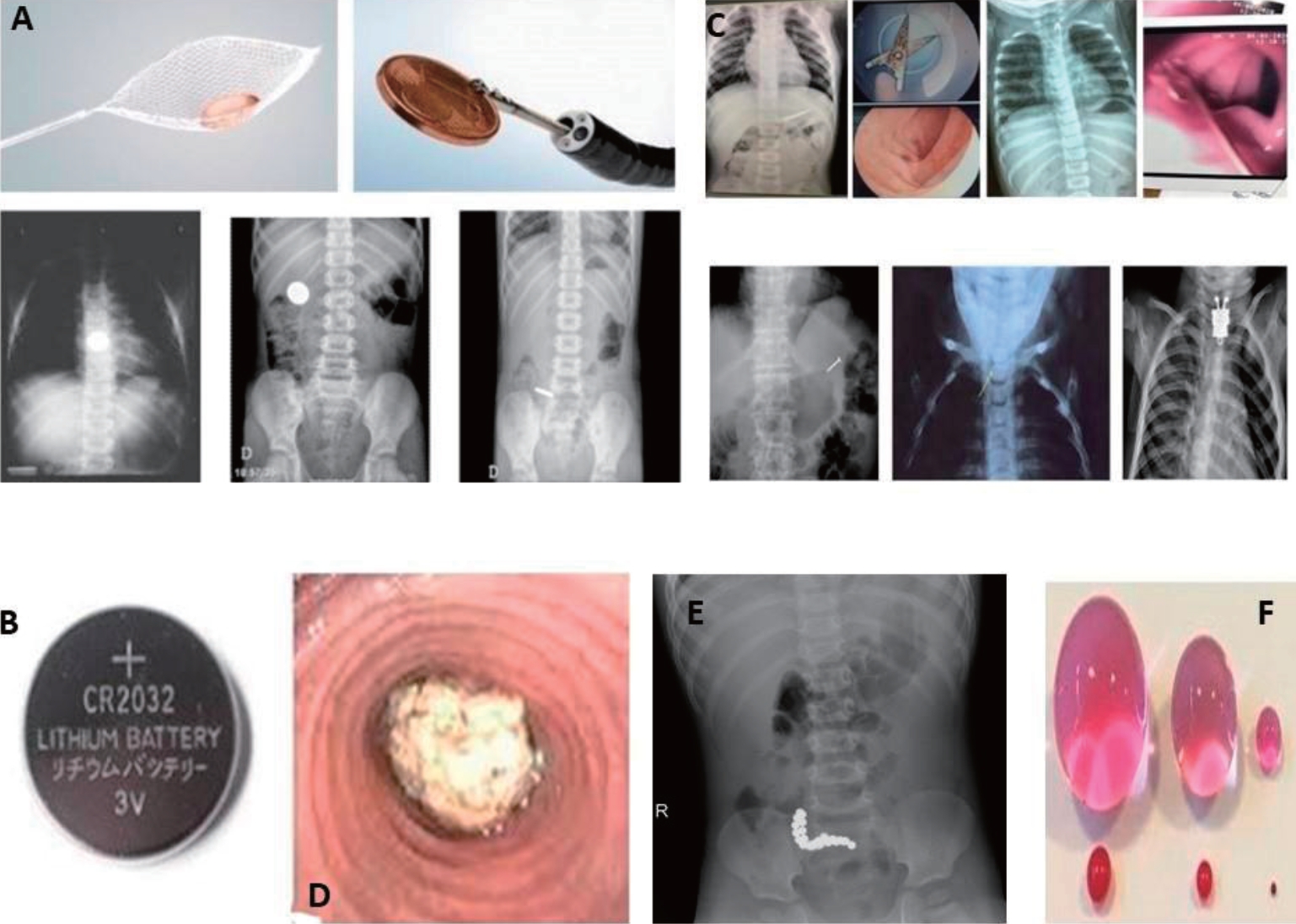

Fig. 1.

(A) Ingested coins. (B) Ingestion battery and resulting esophageal lesions. (C) Different types of sharp items ingested. (D) Food impaction, and esophagus appearingas the trachea with eosinophilic esophagitis. (E) Radiograph of the abdomen, showing the ingested magnets. (F) Superabsorbent polymers.

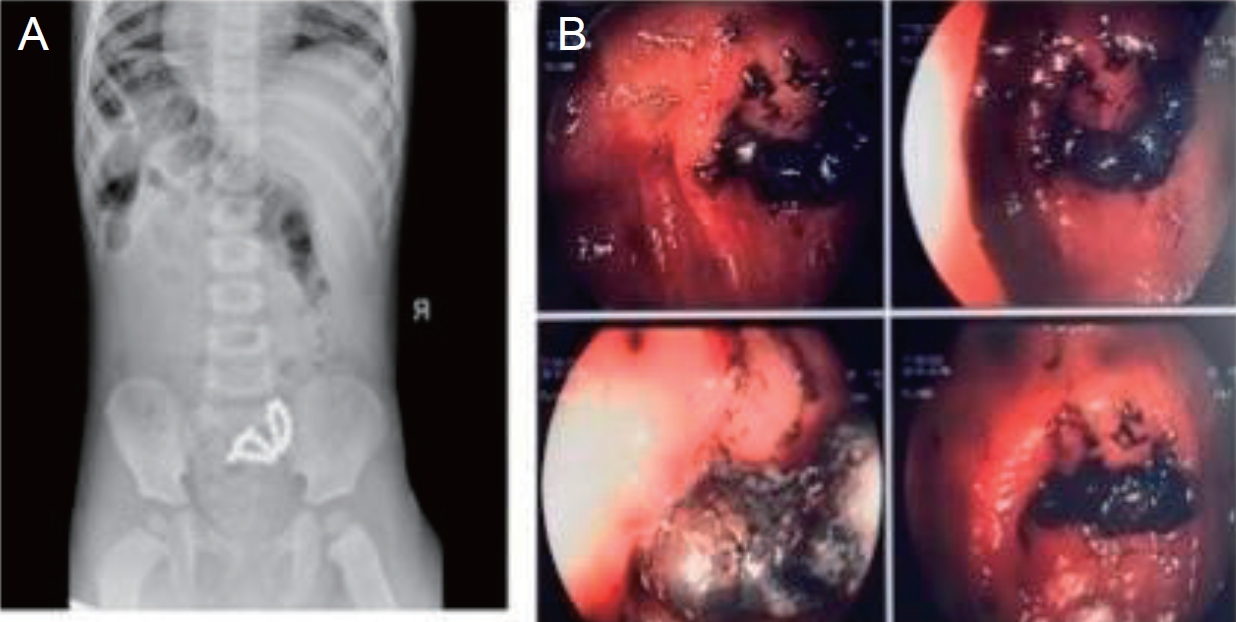

Fig. 2.

(A) Radiograph showing ingested magnets. (B) Endoscopic findings of ingested magnets forming a fistula between intestinal folds.

Fig. 3.

Differentiation between ingested coins and battery. (A) Double-halo sign. (B) Step-off sign (arrow). (C) Ingestion of battery. (D) Esophageal lesions and esophageal necrosis after battery ingestion.

Fig. 4.

Different instruments used for foreign body extraction. (A) Types of forceps. (B) Prophylactic coverage of endoscope for extraction of very sharp objects. (C) Foreign body collection.

Table 1.

Indications for immediate removal of foreign bodies from children

Table 2.

Algorithm: management of foreign body ingestion in children

Table 3.

Algorithm directing management of caustic substance ingestion in children

Table 4.

Latest guidelines concerning foreign body ingestion and caustic substance ingestion in children

| Organization/author | Title/document | Year/status | Scope & relevance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESPGHAN & ESGE | Pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy & foreign body/corrosive Ingestion Guidelines | 2017 | Recommendations for endoscopy timing, corticosteroid use, managing corrosive ingestion. | [42] |

| Ongoing/recent updates | ||||

| Italian SIGENP + AIGO | Foreign Body and Caustic Ingestions in Children: A Clinical Practice Guideline | 2020 | Practical guidelines focused on the role of endoscopists in managing foreign body and caustic ingestion; includes types like button battery, magnets, food impaction. | [8] |

| Global/FISPGHAN Expert Panel | Global Insights on the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Pediatric Ingestions | 2024-2025 | Broad, global expert panel recommendations combining foreign body ingestion and caustic ingestion, red flag identification, urgent removal criteria. | [13] |

References

3. Banerjee R, Rao GV, Sriram PV, Reddy KS, Nageshwar Reddy D. Button battery ingestion. Indian J Pediatr 2005;72:173-4.

4. Bolia R, Sarma MS, Biradar V, Sathiyasekaran M, Srivastava A. Current practices in the management of corrosive ingestion in children: a questionnaire-based survey and recommendations. Indian J Gastroenterol 2021;40:316-25.

5. Hoffman RS, Burns MM, Gosselin S. Ingestion of caustic substances. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1739-48.

6. Waltzman ML, Baskin M, Wypij D, Mooney D, Jones D, Fleisher G. A randomized clinical trial of the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics 2005;116:614-9.

7. Kramer RE, Lerner DG, Lin T, Manfredi M, Shah M, Stephen TC, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: a clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;60:562-74.

8. Oliva S, Romano C, De Angelis P, Isoldi S, Mantegazza C, Felici E, et al. Foreign body and caustic ingestions in children: a clinical practice guideline. Dig Liver Dis 2020;52:1266-81.

9. Reilly S, Carr L. Foreign body ingestion in children with severe developmental disabilities: a case study. Dysphagia 2001;16:68-73.

10. Tran C, Nunez C, Eslick GD, Barker R, Elliott EJ. Complications of button battery ingestion or insertion in children: a systematic review and pooled analysis of individual patientlevel data. World J Pediatr 2024;20:1017-28.

11. Chen QJ, Wang LY, Chen Y, Xue JJ, Zhang YB, Zhang LF, et al. Management of foreign bodies ingestion in children. World J Pediatr 2022;18:854-60.

12. Denney W, Ahmad N, Dillard B, Nowicki MJ. Children will eat the strangest things: a 10-year retrospective analysis of foreign body and caustic ingestions from a single academic center. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:731-4.

13. Manfredi MA, Alvarez RP, Arai K, Cheema HA, Darma A, Elawad M, et al. Global insights on the diagnosis, management, and prevention of pediatric ingestions: a report from the FISPGHAN expert panel. JPGN Rep 2025;6:274-87.

14. Litovitz T, Schmitz BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: an analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics 1992;89:747-57.

15. Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, White NC, Marsolek M. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics 2010;125:1168-77.

16. Tanaka J, Yamashita M, Yamashita M, Kajigaya H. Esophageal electrochemical burns due to button type lithium batteries in dogs. Vet Hum Toxicol 1998;40:193-6.

17. Başer M, Arslantürk H, Kisli E, Arslan M, Oztürk T, Uygan I, et al. Primary aortoduodenal fistula due to a swallowed sewing needle: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2007;13:154-7.

18. Isa HM, Aldoseri SA, Abduljabbar AS, Alsulaiti KA. Accidental ingestion of foreign bodies/harmful materials in children from Bahrain: a retrospective cohort study. World J Clin Pediatr 2023;12:205-19.

19. Pinero Madrona A, Fernández Hernández JA, Carrasco Prats M, Riquelme Riquelme J, Parrila Paricio P. Intestinal perforation by foreign bodies. Eur J Surg 2000;166:307-9.

20. Lao J, Bostwick HE, Berezin S, Halata MS, Newman LJ, Medow MS. Esophageal food impaction in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003;19:402-7.

21. Smith CR, Miranda A, Rudolph CD, Sood MR. Removal of impacted food in children with eosinophilic esophagitis using Saeed banding device. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;44:521-3.

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Gastrointestinal injuries from magnet ingestion in children-- United States, 2003-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55:1296-300.

23. De Roo AC, Thompson MC, Chounthirath T, Xiang H, Cowles NA, Shmuylovskaya L, et al. Rare-earth magnet ingestion-related injuries among children, 2000-2012. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013;52:1006-13.

24. Khalaf RT, Gurevich Y, Marwan AI, Miller AL, Kramer RE, Sahn B. Button battery powered fidget spinners: a potentially deadly new ingestion hazard for children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;66:595-7.

25. Zamora IJ, Vu LT, Larimer EL, Olutoye OO. Water-absorbing balls: a "growing" problem. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1011-4.

27. Moammar H, Al-Edreesi M, Abdi R. Sonographic diagnosis of gastric-outlet foreign body: case report and review of literature. J Family Community Med 2009;16:33-6.

28. Muensterer OJ, Joppich I. Identification and topographic localization of metallic foreign bodies by metal detector. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:1245-8.

29. Schlesinger AE, Crowe JE. Sagittal orientation of ingested coins in the esophagus in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;196:670-2.

30. Salmon M, Doniger SJ. Ingested foreign bodies: a case series demonstrating a novel application of point-of-care ultrasonography in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013;29:870-3.

32. Anfang RR, Jatana KR, Linn RL, Rhoades K, Fry J, Jacobs IN. pH-neutralizing esophageal irrigations as a novel mitigation strategy for button battery injury. Laryngoscope 2019;129:49-57.

33. Mubarak A, Benninga MA, Broekaert I, Dolinsek J, Homan M, Mas E, et al. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of button battery ingestion in childhood: a European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition position paper. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2021;73:129-36.

34. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, Dibert KW, et al. 2019 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 37th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2020;58:1360-541.

35. Irlayıcı FI, Elmas A, Akcam M. Corrosive substance ingestion in children: clinical features, management and outcomes in a tertiary care setting. Eur J Pediatr 2025;184:549.

36. Gordon ES, Barfield E, Gold BD. Early management of acute caustic ingestion in pediatrics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2025;80:537-48.

37. Gupta SK, Croffie JM, Fitzgerald JF. Is esophagogastroduodenoscopy necessary in all caustic ingestions? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;32:50-3.

38. Boskovic A, Stankovic I. Predictability of gastroesophageal caustic injury from clinical findings: is endoscopy mandatory in children? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:499-503.

39. Ateş U, Göllü G, Ergün E, Serttürk F, Jafarov A, Bülbül M, et al. Corrosive substance ingestion: when to perform endoscopy? J Paediatr Child Health 2025;61:967-73.

40. Ozcan C, Ergün O, Sen T, Mutaf O. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to acid ingestion in children. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:1651-3.

41. Park KS. Evaluation and management of caustic injuries from ingestion of acid or alkaline substances. Clin Endosc 2014;47:301-7.

42. Thomson M, Tringali A, Dumonceau JM, Tavares M, Tabbers MM, Furlano R, et al. Paediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy: European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64:133-53.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation