Introduction

Sjogren-Larsson Syndrome (SLS) is a rare autosomal recessive, neuro-cutaneous disorder characterized by a triad of ichthyosis, spastic diplegia or quadriplegia, and mental retardation1). Seizure, short stature, developmental delay, dysarthria, and pigmentary degeneration in the macular region of the retina (Glistening white dots), are other findings which may be associated with this syndrome2). Most individuals with SLS have leukoencephalopathy, which may contribute to its neurological signs and symptoms. The prevalence of SLS is 1 per 250,000 individuals in Sweden where this syndrome was first observed1). Worldwide incidence is estimated to be 0.4 per100, 000 people3). ALDH3A2 gene mutation is recognized as the key defect in SLS, which leads to deficiency of the microsomal enzyme fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase (FALDH)4). This enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of fatty aldehyde to fatty acid. In particular, FALDH dysfunction leads to impaired oxidation of fatty aldehyde to fatty acid and accumulation of fatty alcohols, aldehyde-modified macromolecules, and development of high concentrations of biologically active lipids that have been assumed to be responsible for SLS manifestations5). With regards to FALDH, leukotriene B4 (LTB4) is a key molecule and a pro-inflammatory mediator in developing allergic diseases, especially asthma and is the substrate for the FALDH enzyme6). An increased level of LTB4 has been reported in SLS patients6). Herein, we report a case of SLS with recurrent pneumonia, and asthma, probably due to increased level of LTB4. As far as we are aware, this is the first report of SLS associated with asthma, and recurrent pneumonia.

Case report

A 2-year-old boy was referred to our hospital due to developmental delay, ichthyosis, asthma, and recurrent pneumonia. His parents were related but there was no history of asthma, and allergic disorders in his family, and close relatives. He had ichthyosis at birth, and mild intermittent asthma, and 2 episodes of pneumonia also were observed in his first year of life. He had no history of seizure. His physical examination revealed spastic diplegia and brisk deep tendon reflexes in lower limbs. He was not able to stand or walk, independently and his speech was limited to 2–3 meaningful words.

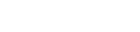

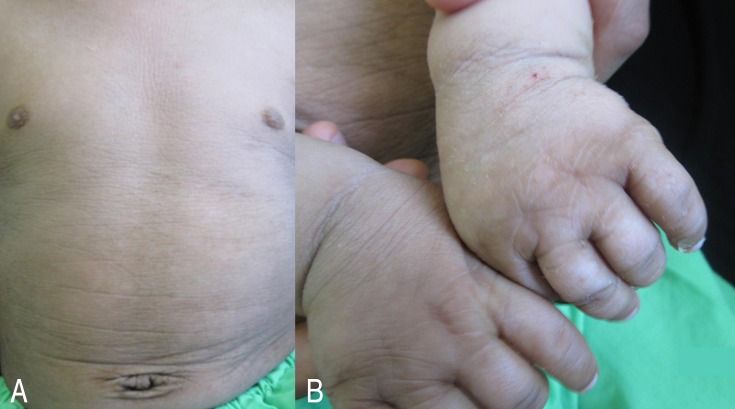

Acquisition of other developmental skills was mildly delayed with achieving head control and sitting without support at 5 and 12 months, respectively. Extensive hyperkeratosis and scaling of the skin were seen particularly in the dorsum of hands, skin flexures, and lower abdomen (Fig. 1). Funduscopic examination was normal.

Electroencephalography, routine laboratory tests, and chromosomal study were also normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated high-intensity lesions in the deep white matter around the trigons of lateral ventricles (Fig. 2). Histopathology of the skin biopsy showed hyperkeratosis with keratotic plugging and parakeratosis consistent with ichthyosis. Molecular genetics study utilizing sequencing of the polymerase chain reaction product using the exon-specific primers revealed a c.370-372 (GGA) deletion mutation in the second exon of ALDH3A2 gene in a homozygote state.

Therefore, the diagnosis of SLS was confirmed. The patient was treated, symptomatically with inhaled corticosteroid, and bronchodilator, local paraffin applicants, and rehabilitation therapy.

Discussion

SLS is estimated to be observed in 1 per 100 and 2,500 patients with mental retardation and dermatologic disorders, respectively7).

The primary defect in SLS is mutation of ALDH3A2 gene, responsible for production of FALDH, an enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of fatty aldehydes to fatty acids. This defect leads to deposition of lipid metabolites in the tissues7). The accumulation of fatty acids in the skin destroys the transepidermal water barrier, and leads to ichthyosis and desquamation. Dermatologic disorders of SLS usually present at birth. Periumbilical region, neck and flexures are, mostly affected, and face is usually spared as in our case. Pruritus is persistent, and more prominent than any other type of ichthyosis.

LTB4 is a potent pro-inflammatory mediator and its production is increased in allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and asthma8). It is synthesized from arachidonic acid, and inactivated by microsomal omega-oxidation.

Asthma might ensue in SLS as the result of increased level of LTB4 secondary to impaired FALDH. This might be the etiology of presentation of asthma in our patient6).

The diagnosis of asthma in early childhood is challenging, and is based largely on clinical judgment, assessment of symptoms, and physical findings. According to Global Initiative for Asthma guideline the diagnosis of asthma is highly suggested in under 5-year group if frequent episodes of wheeze, nocturnal cough in periods without viral infections, and absence of seasonal variation in wheeze has occurred as did occurred in our patient9). In addition he responded to the inhaled corticosteroid and bronchodilator and his respiratory signs and symptoms were controlled with these drugs, every time he experienced acute attacks of wheezing. He had past history of atopic dermatitis in neonatal period and early infancy but examination for allergic sensitization had not been performed for him. We did not perform bronchoscopy for our patient, so we could not report the level of LTB in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Based on Asthma Predictive Index (API) a positive stringent API index requires recurrent episodes of wheezing (3 episodes/yr) during the first 3 years of age and one of two major criteria (physician-diagnosed eczema or parental asthma) or 2 of 3 minor criteria (physician-diagnosis allergic rhinitis, wheezing without colds, or peripheral eosinophilia 4%)10). Our patient had recurrent episodes of wheezing and one major criteria of eczema and 1 minor criteria of wheezing without colds.

Recurrent pneumonia is defined as 2 episodes in a single year or 3 episodes ever, with radiographic clearing of densities between occurrences11). The diagnosis of recurrent pneumonia in our patient was established based on the history of 2 episodes of pneumonia during a single year. Every episode of pneumonia was diagnosed based on respiratory signs and symptoms, auscultatory findings in addition to pulmonary infiltration on chest X-ray reported as pneumonia by the radiologist. Radiologic diagnosis of pneumonia was confirmed by 2 separate radiologists.

Neurologic deficit in SLS is observed with progressive delay in motor development, long tract signs, and spasticity, mostly affecting the lower limbs. Cognitive development is slow and mild to moderate mental retardation and speech problems usually are noted12). Dermatologic and neurologic manifestations of our patient were compatible with this syndrome. Epilepsy is seen in 30%–50% of patients, and usually develops later in childhood but our patient had no history of seizure2).

MRI of brain usually shows mild to moderate brain atrophy, and retarded myelination in the anterior centrum semiovale as was observed in our patient2).

Diagnosis of SLS is made by the presence of the classic triad and confirmed by enzyme assay, and/or genetic study. Analysis of LTB4 and its metabolites in urine has offered a new, noninvasive and low-cost diagnostic test6). Treatment is supportive, and includes the use of emollients, keratolytics, systemic retinoids, and rehabilitation therapy. Some studies report leukotriene synthesis inhibitors as possible therapeutic agents for dermatologic symptoms13). Other findings show that gene therapy may be a treatment option in the future14).

In conclusion, pediatricians should be aware and evaluate patients with SLS for possible associated asthma, and allergic disorders.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation