< Previous Next >

Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 59(2); 2016 |

|

Abstract

Patients with hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) can rapidly develop profound anemia as the disease progresses, as a consequence of red blood cell (RBC) hemolysis and inadequate erythropoietin synthesis. Therefore, RBC transfusion should be considered in HUS patients with severe anemia to avoid cardiac or pulmonary complications. Most patients who are Jehovah's Witnesses refuse blood transfusion, even in the face of life-threatening medical conditions due to their religious convictions. These patients require management alternatives to blood transfusions. Erythropoietin is a glycopeptide that enhances endogenous erythropoiesis in the bone marrow. With the availability of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO), several authors have reported its successful use in patients refusing blood transfusion. However, the optimal dose and duration of treatment with rHuEPO are not established. We report a case of a 2-year-old boy with diarrhea-associated HUS whose family members are Jehovah's Witnesses. He had severe anemia with acute kidney injury. His lowest hemoglobin level was 3.6 g/dL, but his parents refused treatment with packed RBC transfusion due to their religious beliefs. Therefore, we treated him with high-dose rHuEPO (300 IU/kg/day) as well as folic acid, vitamin B12, and intravenous iron. The hemoglobin level increased steadily to 7.4 g/dL after 10 days of treatment and his renal function improved without any complications. To our knowledge, this is the first case of successful rHuEPO treatment in a Jehovah's Witness child with severe anemia due to HUS.

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a common cause of acute renal injury in young children. It is characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal injury1). The etiology of HUS is variable, including infection, genetic disorder, medication, and other systemic diseases, of which infection is the most common cause of the disease1). Most cases of diarrhea-associated HUS (D(+) HUS) are caused by Shiga toxin-producing bacteria, such as Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) with serotype O157, O111, or O261,2).

Patients with HUS require careful supportive care, including management of fluid and serum electrolyte balance, control of hypertension, and early dialysis in anuric or significantly oliguric states2). However, there are no specific recommended therapies to ameliorate the course of the disease.

Patients with HUS can rapidly become profoundly anemic because of hemolysis of RBC. In addition, it has been reported that erythropoietin synthesis is reduced in patients with HUS, contributing to aggravation of the anemia3). Therefore, HUS with anemia is the standard indication for RBC transfusion to avoid cardiac or pulmonary complications. About 80% of patients with HUS require packed RBC transfusion4).

Here, we report a case of a male child with severe hemolytic anemia due to diarrhea-associated HUS, whose parents refused packed RBC transfusion because they are Jehovah's Witnesses. Instead of packed RBC transfusion, we treated him with rHuEPO with iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12 supplements. He recovered successfully from anemia and kidney injury without any complications.

A 31-month-old male was transferred from a local children's hospital to Yeungnam University Medical Center in Daegu, Korea. For 3 days before transfer, he had been admitted to a local children's hospital for fever, abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea. Based on suspected bacterial colitis, he received intravenous third-generation cephalosporin medication for empirical treatment, but the symptoms did not improve.

At the time of admission, the patient was treated with fluid management and antibiotics management based on a diagnosis of colitis with dehydration. Initial laboratory investigation revealed leukocytosis (white blood cell, 17,760/µL), normal hemoglobin level (Hb, 13.3 g/dL), platelet count of 150×103/µL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level of 11.01 mg/dL, and increased serum creatinine (Cr) level of 0.85 mg/dL. Abdominal computed tomography revealed pancolitis and small amount of ascites and pleural effusion, and there was no evidence of a condition that required surgical treatment.

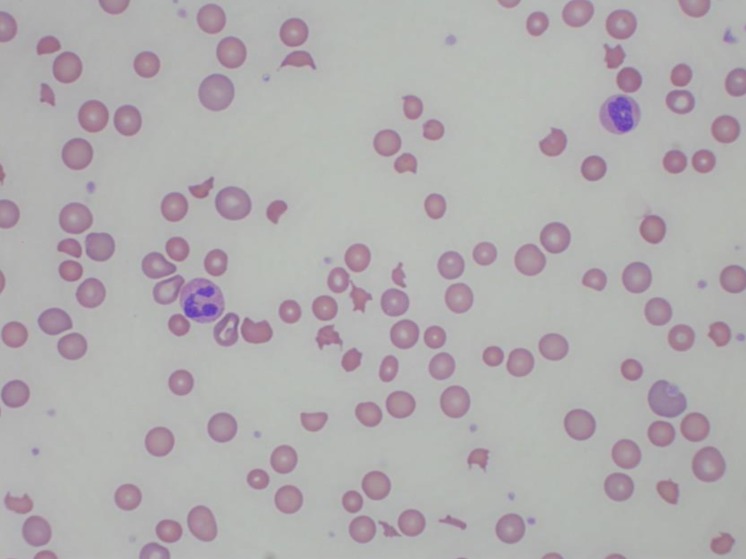

The patient still presented with an ill and lethargic appearance and a large amount of bloody diarrhea on the second day of admission. The urine output was decreasing to the range of oliguria. Follow-up laboratory tests showed decreased hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL, thrombocytopenia (platelet count 40×103/µL) and decreased renal function with a serum Cr level of 1.86 mg/dL. Estimated Cr clearance was 28.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 and fractional Na excretion was 2.2% implying intrinsic renal failure. Hemolytic markers showed a raised reticulocyte level of 3.12 %, raised lactate dehydrogenase of 1,448 U/L, and reduced haptoglobin level of 3 mg/dL (normal range, 22–164 mg/dL). Schistocytes and blurred cells were observed in peripheral blood smear, suggestive of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (Fig. 1). A diagnosis of diarrhea-associated HUS was made, and the patient received careful supportive treatment with no further antibiotics.

On the third day, the oliguric state persisted with rapidly increased BUN and serum Cr level to 40.3 mg/dL and 3.93 mg/dL, respectively. The Hb level decreased to 9.5 g/dL. We decided to perform hemodialysis as renal replacement therapy. Then, we recommended packed RBC transfusion for dialyzer priming volume during hemodialysis. However, the patient's parents refused transfusion of any blood products, including packed RBC, because they were Jehovah's Witnesses. Hemodialysis was performed with a priming process using 20% albumin on days 3 and 4 with the parents' consent. As the anemia progressed, we were unable to perform hemodialysis due to concerns about further blood loss and hypovolemia.

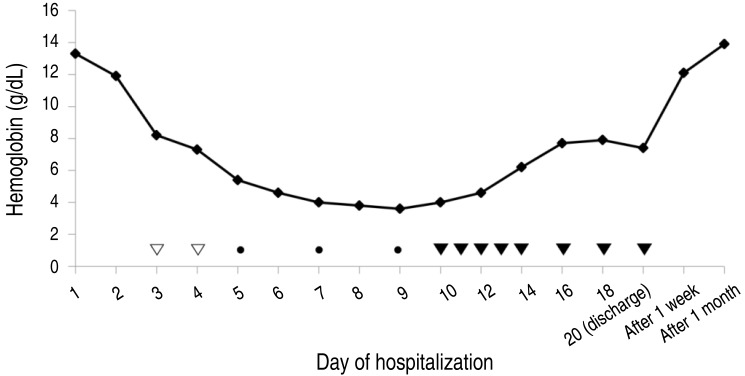

The hemoglobin level decreased to 3.6 g/dL at the lowest on day 9. Eventually, we used high-dose rHuEPO therapy to manage the severe anemia. Erythropoietin β (Recormon, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was administered at a dose of 300 IU/kg/day for the first five consecutive days, after which the same dose was administered every other day. In addition, intravenous iron (3 mg/kg/day, daily), folic acid (1 mg/day, daily), and vitamin B12 (1 mg/day, daily) were given together. The Hb level increased steadily and was normalized 1 week after discharge (Hb, 12.1 g/dL) (Fig. 2). In addition, the serum Cr level and the results of urinalysis recovered to the normal range.

During high-dose rHuEPO therapy, the patient showed stable vital signs. Common adverse events related to rHuEPO therapy, such as flu-like symptoms, hypertension, thrombocytosis, thrombosis, allergic reaction, or seizure, were not observed in this case. Echocardiography revealed mild left atrial enlargement and mild left ventricular hypertrophy but normal ventricular function.

Initial stool culture on sorbitol-containing MacConkey agar detected enterohemorrhagic E. coli serotype O26 and polymerase chain reaction specific for Shiga toxin (stx1 and stx2) was positive.

Patients with D(+) HUS require careful supportive care. The volume status of patients should be monitored carefully to avoid fluid overload or depletion, especially in cases with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake5). Maintaining renal perfusion and avoiding fluid overload are important when azotemia develops. In anuric or significantly oliguric patients, the indications for dialysis are similar to those in other forms of acute kidney injury, and early dialysis can be helpful. The patients can rapidly become profoundly anemic as a consequence of RBC hemolysis and inadequate erythropoietin synthesis3). Many HUS patients with anemia require RBC transfusion to avoid cardiac or pulmonary complications. Platelet transfusion is not recommended unless life-threatening hemorrhage occurs, or an invasive procedure is undertaken, because platelet transfusion can exacerbate thrombosis6). Studies of the use of steroids, antithrombotic agents (aspirin, heparin, dipyridamole, and streptokinase), plasma infusion, plasma exchange, or Synsorb-Pk in HUS patients have been reported; however, none showed a significant treatment benefit7). In addition, antibiotic therapy is discouraged in STEC-infected patients, because it is known to have little benefit and to increase the risk of D(+) HUS2).

Jehovah's Witnesses decline therapeutic transfusion of the primary components of human blood based on their religious beliefs. There are alternative approaches to managing severely anemic patients refusing blood transfusion. These include stopping further blood loss, stimulating erythropoiesis using rHuEPO, maintaining blood volume with intravenous fluids, and other forms of supportive care8). Clinical trials using bioartificial oxygen carriers, especially hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers, are currently ongoing9).

Erythropoietin is a glycoprotein that enhances RBC production in bone marrow. Erythropoietin and its analogs are widely used for anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease and patients who receive chemotherapy. A previous study showed a consistent rise in reticulocyte count within 4–5 days and increased hemoglobin level and hematocrit within 7 days on treatment with rHuEPO10). The optimal dose and dosing regimens are unclear, especially in critically ill patients with severe blood loss or those with severe acute anemia who refuse transfusion. There have been reports of cases in which severe anemia was successfully treated with erythropoietin in patients who refused blood transfusion. However, such cases in children are rare, and in most of these cases anemia was caused by hemorrhage due to trauma or related to surgical procedures11,12). In our case, we referred the report from Digieri et al.11) for the dose of rHuEPO (300 IU/kg/day). To keep up with enhanced erythropoiesis, iron, folate, and vitamin B12 should be added. In addition, adequate nutrition is also important during treatment.

Besides its erythropoietic effect, erythropoietin is known to exert a renoprotective effect by suppressing renal tubular epithelial apoptosis, enhancing epithelial proliferation and hastening functional recovery in ischemic or drug-induced acute kidney injury13). Pape et al.14) reported that early administration of erythropoietin may attenuate anemia and reduce the requirement for RBC transfusion if administered early in the course of hemolytic anemia and renal failure in D(+) HUS patients. However, a recent study showed that rHuEPO therapy had no RBC transfusion-sparing effect in D(+) HUS patients15). Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify the efficacy of rHuEPO in D(+) HUS.

Here, we reported the first case of successful rHuEPO therapy in a Jehovah's Witness child with severe anemia due to D(+) HUS without RBC transfusion. In summary, rHuEPO therapy can be effective in acute anemia due to D(+) HUS, especially in patients in whom RBC transfusion is not possible. In addition to enhancing RBC production, a renoprotective effect of rHuEPO therapy can be expected in patients with D(+) HUS.

Conflicts of interest

Conflicts of interest:

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Scheiring J, Rosales A, Zimmerhackl LB. Clinical practice. Today's understanding of the haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:7–13.

2. Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 2005;365:1073–1086.

3. Exeni R, Donato H, Rendo P, Antonuccio M, Rapetti MC, Grimoldi I, et al. Low levels of serum erythropoietin in children with endemic hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1998;12:226–230.

4. Brandt JR, Fouser LS, Watkins SL, Zelikovic I, Tarr PI, Nazar-Stewart V, et al. Escherichia coli O 157:H7-associated hemolytic-uremic syndrome after ingestion of contaminated hamburgers. J Pediatr 1994;125:519–526.

5. Ake JA, Jelacic S, Ciol MA, Watkins SL, Murray KF, Christie DL, et al. Relative nephroprotection during Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections: association with intravenous volume expansion. Pediatrics 2005;115:e673–e680.

6. Weil BR, Andreoli SP, Billmire DF. Bleeding risk for surgical dialysis procedures in children with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:1693–1698.

7. Trachtman H, Christen E. Pathogenesis, treatment, and therapeutic trials in hemolytic uremic syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr 1999;11:162–168.

8. Remmers PA, Speer AJ. Clinical strategies in the medical care of Jehovah's Witnesses. Am J Med 2006;119:1013–1018.

9. Donahue LL, Shapira I, Shander A, Kolitz J, Allen S, Greenburg G. Management of acute anemia in a Jehovah's Witness patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia with polymerized bovine hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier: a case report and review of literature. Transfusion 2010;50:1561–1567.

10. Feagan BG, Wong CJ, Kirkley A, Johnston DW, Smith FC, Whitsitt P, et al. Erythropoietin with iron supplementation to prevent allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip joint arthroplasty. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:845–854.

11. Digieri LA, Pistelli IP, de Carvalho CE. The care of a child with multiple trauma and severe anemia who was a Jehovah's Witness. Hematology 2006;11:187–191.

12. Akingbola OA, Custer JR, Bunchman TE, Sedman AB. Management of severe anemia without transfusion in a pediatric Jehovah's Witness patient. Crit Care Med 1994;22:524–528.

13. Bahlmann FH, Fliser D. Erythropoietin and renoprotection. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2009;18:15–20.

Fig. 1

Peripheral blood smear of the patient. Peripheral blood smear showing fragmented red blood cells. Schistocytes (helmet cells and triangular cells) were seen, together with polychromasia (Wright stain, ×400).

Fig. 2

Progressive changes in serum hemoglobin levels. Recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) (120 IU/kg/day) was administered on days 5, 7, and 9 at a dose of 120 IU/kg/day. High-dose rHuEPO (300 IU/kg/dose) was given daily from day 10 to day 14, and on alternative days from day 16. Intravenous iron (3 mg/kg/day), folic acid (1 mg/day), and vitamin B12 (1 mg/day) were administered daily during high-dose rHuEPO therapy. The hemoglobin level was lowest on day 9 (3.6 g/dL), and then increased consistently and normalized 1 week after discharge (12.1 g/dL). Hemodialysis was performed on days 3 and 4. •, rHuEPO therapy at a dose of 120 IU/kg/day; ▾, high-dose rHuEPO therapy; ▿, hemodialysis.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation